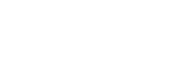

MINING

The discovery of gold in Minas Gerais at the turn of the 17th century to the 18th fostered the already intense trade of enslaved people in Brazil. Transatlantic trafficking doubled in the first half of the 18th century. Between 1701 and 1720, approximately 292,000 enslaved Africans were landed in Brazilian ports and sent mainly to gold mines. From 1720 to 1741, this number also increased significantly, with 312,400 individuals arriving in Portuguese America. In the following two decades, trafficking reached its peak, with 354,000 enslaved Africans being introduced to Portuguese America between 1741 and 1760.

GOLD IN DECLINE, POPULATION ON THE RISE

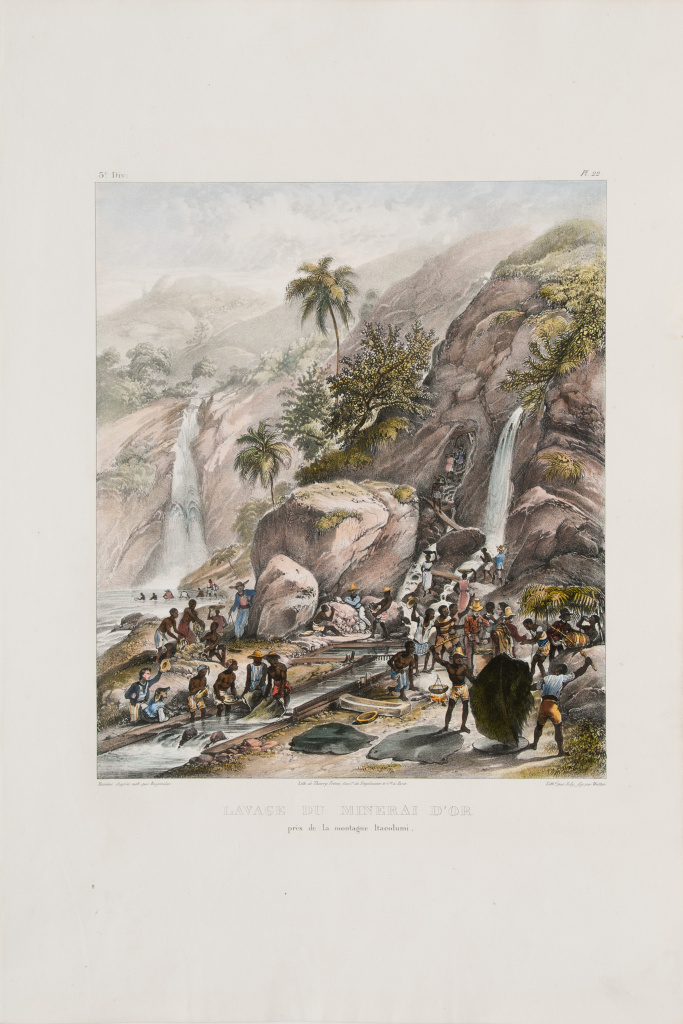

In 1780, gold exploitation in the region began to decline. São João del-Rei, already a hub of agricultural and commercial activity, remained relatively unscathed by economic woes. In a twist of fate, the city experienced growth as it became a magnet for residents from surrounding areas seeking employment opportunities.

The population of the District of Rio das Mortes tripled, jumping from 82,781 in 1776 to 213,617 residents in 1820.

Stories:

“The heart of Minas Gerais exports lay at the commercial square of São João del-Rei, serving as the nucleus for trade. Alongside Barbacena, it formed the twin hubs of wholesale commerce, acting as real regional warehouses. Located on the road of Gerais, they served as the central hub for the flow of goods from different regions, even from Goiás and Mato Grosso. São João del-Rei played a pivotal role in channeling the majority of the state’s subsistence exports, while Barbacena emerged as a primary center for cotton exports”.

Alcir Lenharo, in “As tropas da Moderação: O abastecimento da Corte na formação política do Brasil: 1808-1842” (The Moderation Troops: Supplying the Court during Brazil’s Political Formation, 1808-1842), published in 1993

“The city of S. João d’el Rey, 8 miles distant from S. José, was also celebrated for the amount of gold it produced, particularly gold that was extracted from mining pits, in which tradition has provided the most extraordinary stories; […]; Serra do Lenheiro (Lenheiro Mountain Range) unfolded before us, stretching like that of São José, with harsh peaks of perpendicular rocks, yet more irregular and scattered. Within a knot of these formations, we reached the bridge that spans the Rio das Mortes. The impression of being in a prosperous and flourishing city, where the majority of mercantile houses consisted of shops with well-maintained appearances and filled with goods from various origins, mainly china and items from England, bales of raw cotton, and stacks of coarse felt hats, not to mention a variety of other goods produced in the region.”

Robert Walsh, physician and chaplain of the British colony in Rio de Janeiro, who during the years 1828 and 1829 visited and described events in the colony.

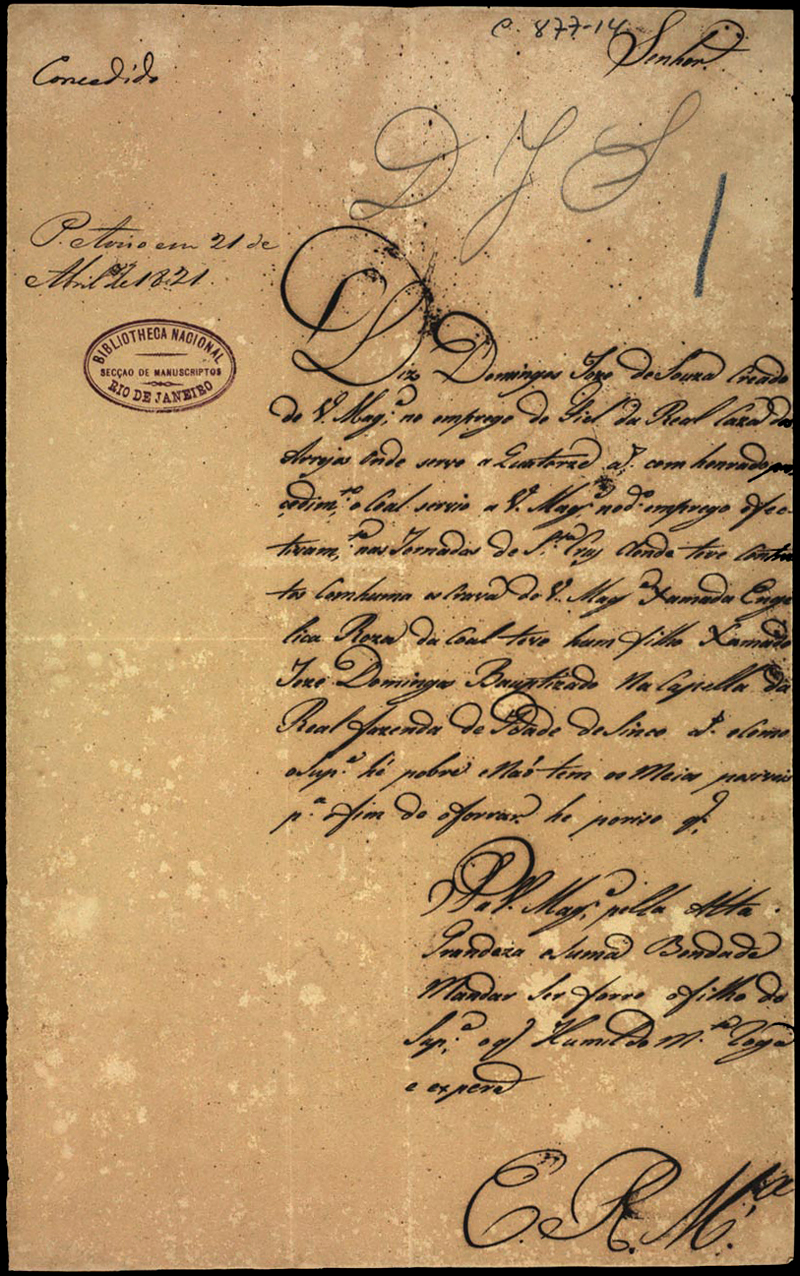

THE DECLINE OF GOLD AND THE ERA OF MANUMISSION

As gold mining declined, slave ownership became less profitable for the explorers. Therefore, manumission, the act of freeing slaves from bondage, was made easier and became more common during this time. The surplus enslaved population was swiftly integrated into agropastoral activities through manumission. According to books at the São João del-Rei Notary Public Office (1754-1831), 382 manumissions were reviewed, granted in the decade spanning 1801-1810. The primary type of manumission was paid manumission, comprising 156 cases, followed by free/conditional manumissions, with 82 being unconditional and the remainder being conditional. Conditional manumissions are those that involve certain conditions, such as “payment, provision of services, fulfillment of religious obligations (such as paying for masses for the soul of the testator, friends, relatives, and souls in purgatory), among others.” In the case of payment, it could be made in cash, through the delivery of a new captive to the master, or through coartation, where freedom was granted gradually in exchange for services. The opportunity for manumission arose from economic necessity. The Black people in São João played a crucial role in the city’s economic expansion, actively participating in trade, services, and the consumption of goods.

Dados e informações extraídas da tese de doutorado de Cristiano Lima da Silva, intitulada Entre batismos, testamentos e cartas: as alforrias e as dinâmicas de mestiçagens em São João del-Rei (c.1750-c.1850).

Story:

“Manumission was never truly free. Even if no money was exchanged or services provided for freedom, the enslaved individual had already contributed value to the master throughout their life in bondage, without receiving an equivalent exchange of value in return.”.

Peter Eisenberg, in his book Homens Esquecidos: Escravos e Trabalhadores Livres no Brasil – Séculos XVII e XIX (Forgotten Men: Slaves and Free Workers in Brazil – 17th and 19th Centuries).

THE PILLORY OF SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI

Pillories stand out as symbolic pillars of the Portuguese crown’s authority and the brutality of slavery. Constructed from stone, wood, or metal, they were erected in colonial squares or villages as a site for public punishment. Colonial authorities would administer physical punishments to enslaved individuals and transgressors. Flogging and other punitive measures served as displays of power and control over public order, aimed at suppressing certain behaviors. To bolster colonial authority further, these pillars often displayed coats of arms.

Most pillories were destroyed or removed after abolition. São João del-Rei stands as one of the few cities in the country that keeps its pillar intact. Today, the monument serves as a historical testament to the colonial era and underscores the imperative for historical reparations for the violence inflicted upon Black people during slavery.

WHO ARRIVED IN BRAZIL?

Numerous African ethnic groups were transported to Brazil via the transatlantic slave trade, orchestrated by European powers like Portugal and England. These nations established trading posts across Africa, where they procured slaves from diverse ethnic backgrounds and subsequently transported them to the Americas. Upon arrival, these individuals were subjected to forced labor in plantations, mines, and other economic endeavors. This trade profoundly disrupted and devastated African communities, resulting in a far-reaching African diaspora with enduring consequences. Enslaved individuals were compelled to forsake not only their homelands but also their cultural traditions, languages, and social structures, confronting daunting challenges in the Americas. Here, they were categorized according to what was referred to as “qualities.”

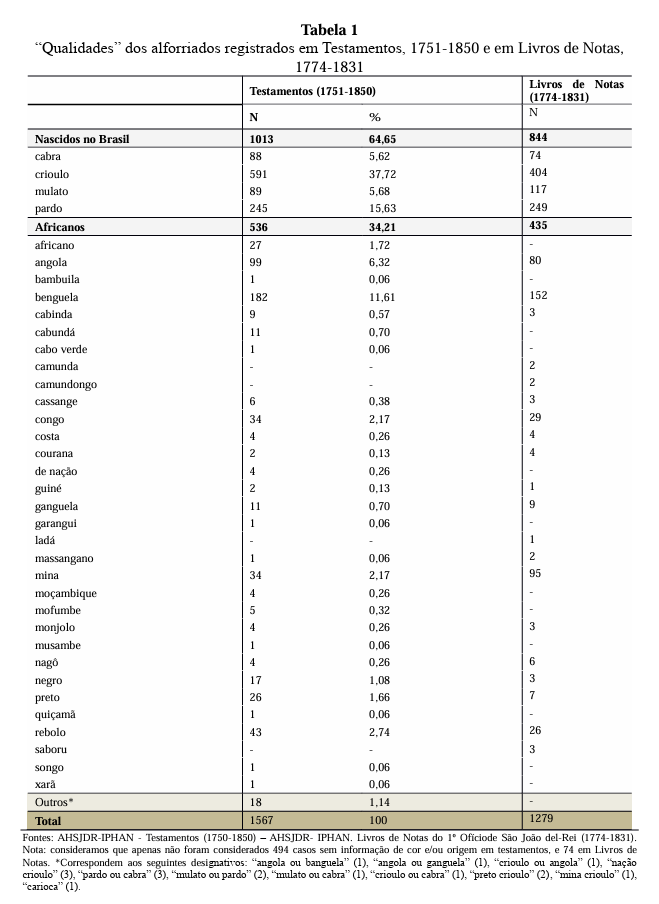

Next, you can examine the classifications of freed enslaved individuals recorded in wills between 1751 and 1850, as well as those documented in the books from the Notary Public Office from 1774 to 1831, in São João del-Rei. It’s important to note that when documents mention Africans arriving in Brazil under specific names, these names may be associated with the region of capture or the ports from which they embarked towards Brazil, rather than their actual ethnic origins.

ENSLAVED PEOPLE BORN IN AFRICA – “NATION SLAVE”

“Nation slave” typically refers to the place of embarkation or imprisonment of enslaved African individuals. It does not necessarily denote their specific ethnic identification or exact geographical origin. The designations commonly indicated the territories from which they had been captured or shipped, such as Cape Verde, Angola, etc.

Sometimes, enslaved individuals identified strongly with the ethnic group corresponding to their classification. An example of this can be found in the records from 1803 of the Irmandade de Nossa Senhora do Rosário dos Pretos (Brotherhood of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Blacks) in São João del-Rei. These records contain entries for masses dedicated to the “Noble Benguela Nation,” indicating that the Benguela people formed a group with its own identity and autonomy. Interestingly, the Brotherhood also recorded entries for individuals who identified with other ethnic groups, such as Ganguela, Monjolo, and Songa, among others.

In the Judicial District of Rio das Mortes, the most found classifications are Minas and Benguelas. Let’s delve deeper into these groups and explore others as well.

ENSLAVED PEOPLE BORN IN BRAZIL

Enslaved individuals were often categorized based on their origins, such as their place of birth, capture, or the port from which they were shipped. Yet, skin color played a critical role in assessing their “quality.” Particularly for those born in Brazil, their classification was deeply influenced by their color. Let’s delve into some of these categorizations.